- Home

- Melissa Katsoulis

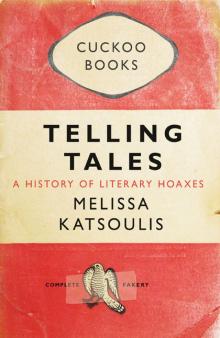

Telling Tales

Telling Tales Read online

Melissa Katsoulis is a journalist and writer. She has written for The Times, where she also worked on the books desk, the Sunday Telegraph, the Financial Times, The Tablet and the Ham and High. She lives in London.

Telling Tales

A HISTORY OF LITERARY HOAXES

by

MELISSA KATSOULIS

CONSTABLE • LONDON

For Rosalind Adams: mother, friend, investor

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2009

Copyright © Melissa Katsoulis, 2009

The right of Melissa Katsoulis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

The extract on page 61 is from Prince of Forgers by Joseph Rosenblum, 1998, Oak Knoll Press

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-84901-080-1

eISBN: 978-1-47210-783-1

Printed and bound in the EU

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 The Eighteenth Century

William Lauder – James Macpherson – Thomas Chatterton – William Henry Ireland

2 The Nineteenth Century

Maria Monk – The Protocols of the Elders of Zion – Vrain-Denis Lucas – Mark Twain – Sir Edmund Backhouse

3 Native Americans

Grey Owl – Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance – Forrest Carter – Nasdijj

4 Celebrity Testaments

The Abraham Lincoln Letters – The JFK Letters – The Autobiography of Howard Hughes – The Hitler Diaries

5 Australia

Ern Malley – Nino Culotta – Marlo Morgan – Helen Demidenko – Norma Khouri – Wanda Koolmatrie

6 Memoirs

Joan Lowell – Cleone Knox – Beatrice Sparks – Laurel Rose Willson – Anthony Godby Johnson – J.T. LeRoy – Tom Carew – Michael Gambino – James Frey – Margaret B. Jones

7 Post-Modern Ventriloquists

Fern Gravel – Araki Yasusada – Andreas Karavis

8 Holocaust Memoirs

Binjamin Wilkomirski – Misha Levy Defonseca – Herman Rosenblat

9 Religion

Johannes Wilhelm Meinhold – Robert Coleman-Norton – Morton Smith – Pierre Plantard – Mark Hofmann

10 Entrapment Hoaxes

Harold Witter Bynner and Arthur Davison Ficke – H.L. Mencken – Nicolas Bataille and Akakia Viala – Jean Shepherd – Mike McGrady – Romain Gary – Alan Sokal – Bevis Hillier – William Boyd

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Gina Rozner, without whom this book would not exist, and also to Andreas Campomar and everyone at Constable. I am grateful to Margaret Body, Giles Coren, Alison Flood, Chaz Folkes, Ivan Helmer, Nicolas Madelaine, Angela Martin, Neel Mukherjee, Michael Prodger, Pete Rozycki, Jerry Sokol, Guy Stevenson, Erica Wagner, Carl Wilkinson. And to Peter Stevenson: the greatest living Greek Scotsman and the love of my life.

INTRODUCTION

FROM DISGRUNTLED MORMONS and fake Native Americans to bored students and lustful aristocrats, the bizarre history of literary hoaxers is every bit as revealing as the orthodox roll-call of Western writers, as is their acute appreciation of what inspires, frightens and resonates with their generation. And their stories are often incredibly funny, too.

This history of the most notable literary hoaxes does not claim to be comprehensive: some well-loved tricksters such as Henry Root and Rochester Sneath have been left out because they seem, on reflection, to be more practical jokers than true hoaxers. Others, like Thomas J. Wise and James Collier, are not included because their rather pedestrian projects must be called forgeries rather than hoaxes. And although it begins in the eighteenth century – the age of the novel and the era when being a publisher or author offered, for the first time, a real chance at what Samuel Johnson called ‘the fever of renown’ – cases of writers playing games with authorship and authenticity can be traced as far back as the fourth century BC.

Some were hoaxing for their own amusement, as was the case with the philosopher known as Dionysius the Renegade, the earliest hoaxer literary history records. He was the spirited rebel Stoic who, after breaking away from the school which had raised him to believe in the nobility of pain and suffering, manufactured a fake Sophocles play called Parthenopaeus and inserted into it a number of insulting acrostics including ‘HERACLIDES IS IGNORANT OF LETTERS AND IS NOT ASHAMED OF HIS IGNORANCE’.

Others, such as the unknown author of the famous Donation of Constantine, hoaxed for political gain: that two-part document comprising the Confessio and Donatio which was inserted into a twelfth-century book of canonical law purported to confirm the Emperor Constantine’s gift of European dominion to the church in return for Pope Sylvester curing him of leprosy and revealing to him Christ’s love.

To understand the significance of the stories collected here (most of which can and should be read as much for sheer amusement at the amazing lengths to which people will go to practise a deception, and the sheer nonsense gullible readers are willing to swallow, as for literary-historical edification) it is useful to consider the three main types of hoax, and the thorny subject of truth-telling in literature more generally.

Not all hoaxes are equal and although the ones chosen for inclusion in this book are arranged chronologically within chapters, they might just as easily have been broken down into the three distinct groups that most hoaxes can be said to fall into. The American academic Brian McHale, one of the surprisingly few literary theorists to attempt a comprehensive taxonomy of the written hoax, has identified these groups as: the genuine hoax, the entrapment hoax and the mock hoax.

Into the first group fall the majority of examples, and nearly all of the very famous ones. The Hitler Diaries, the Ossian poems, William Ireland’s Shakespeare papers and the Donation of Constantine can all be given McHale’s playfully oxymoronic label ‘genuine hoax’ because they are dishonest literary creations which are intended never to be exposed. They might be done for reasons of financial, ideological or emotional gain, but they are neither self-conscious works of art nor are they intended to poke fun at specific individuals or institutions. The perpetrators of these hoaxes tend to be unfortunate creatures who have been unable to find success with their legitimate works and who are desperate either for the money or recognition that literary success can bring. The eighteenth century’s William Ireland is a prime example: he was a boy growing up in London amidst the 1790s frenzy for collecting and classifying European cultural artefacts. Studiously ignored by his bibliophile father, he was considered dim and hopeless and forced into a humble clerking job which he hated. Yet on the day he first presented his Shakespeare-obsessed parent with a piece of paper purporting to bear the bard’s signature, all his life’s problems began to evaporate. Overnight, he became the focus of his father’s undivided attention, praised for his brilliance in sourcing and negotiating deals for the series of Shakespearean papers he was secretly producing using antique paper and specially mixed ink.

The main reason for Ireland’s eventual undoing was that he was not a skilled enough writer t

o convince critics that his ‘discovered’ works were genuine. Other pliers of ‘genuine hoaxes’, however, were such skilled stylists that their work has continued to be held in high regard even after debunking and death. Thomas Chatterton’s Rowley poems and the bardic verses by Macpherson are both cases in point, and continue to be read and studied today as worthwhile creations in their own right; and particularly in the case of Chatterton, the ill-fated young medievalist from Bristol who came to London to seek his fortune but fell victim to poverty and desperation before his talents could out, the high romance of the hoaxer’s real-life story has proved irresistible to future generations. Of all the hoaxers who have caught the imagination of later writers (Ern Malley and Anthony Godby Johnson’s appearance in novels by Peter Carey and Armistead Maupin being other examples) the life of Chatterton has continued to inspire great secondary works of art by authors from John Keats to Peter Ackroyd.

Perhaps the boldest ‘genuine hoax’ is one of the least known, and dates from fifteenth-century Italy. It involves a monk called Annius from Viterbo, near Rome, who so loved his hometown that he stopped at nothing to prove his patriotism – not at planting faked Etruscan fragments of pottery in his neighbour’s earth, not at claiming to have discovered hugely significant lost writings by the early religious writer Berosus which claimed that Viterbo was where Noah’s offspring first repopulated the world with Aryans after the flood. Nearly a century later his hoaxes were debunked, using the same new forensic critical techniques which exposed the Donation of Constantine: careful line-byline analysis of vocabulary, orthography and parallel texts. And no small amount of common sense.

Chatterton and his ilk might be tragic figures, but the second group of hoaxers has left a body of work more likely to inspire glee than sympathy. These are the people whose intention is to lure a particular academic, publisher or literary community with a prank text and then reveal (often through clues planted in the manuscript itself) how stupid its readers were to believe it – and, by extension, how clever the hoaxer was to trick them. The most famous hoax in Australia – and indeed in twentieth-century English-language poetry in general – was the invented oeuvre of Ern Malley, secretly written by a pair of disgruntled young traditional poets, James McAuley and Harold Stewart, who claimed at the time to have dashed off the ultra-modernist poems in an afternoon. (They almost certainly did not, and ironically are now considered to have produced some of their best work under the Malley name.) They were neither the first nor last group of twentieth-century writers to create bogus texts to make a dismissive point about the cultural fads of their day, and all of their ilk reveal as much about their target audience as they do about themselves. Particularly the Spectra poetry hoax in 1916 (the motivation behind which was similar to McAuley and Stewart’s) and the superbly awful erotic novel Naked Came the Stranger in 1969, which set out to prove that as long as a book was full of sex it need have no literary merit to succeed. And it is not only lovers of fashionable fiction who get pricked by the hoaxer’s barb: when the physicist Alan Sokal successfully submitted a paper composed of pseudo-sociological gibberish to a leading cultural studies journal in the mid-1990s, he proved spectacularly that the entrapment hoax was alive and well. Then, in 2006, the official biographer of John Betjeman hid the immortal words ‘A N WILSON IS A SHIT’ in a fake Betjeman love-letter which he submitted to his rival biographer under the anagrammatic name ‘Eve de Harben’, which was blithely included in the first edition of Wilson’s work on the poet. The entrapment hoaxes, although deliberately bringing disrepute to fellow professionals, are certainly some of the most fun to read, and constitute an un-sobering reminder of the value of play and theatre in the often self-important business of publishing and academia.

The final group is also the smallest, but that may not be the case forever. ‘Mock hoaxes’ are those in which a genuinely experimental writer plays conscious tricks with the very notion of authorship to create a voice which is neither quite theirs nor someone else’s. It is the kind of literary ventriloquism we see in the work of Fern Gravel, the ten-year-old girl-poet who gained a cult following in mid-twentieth-century America but was, in truth, an ageing, male writer of adventure stories; the Canadian poet who could only cure his writer’s block by adopting the persona of a grizzled Greek fisherman called Karavis; and the eccentric academic almost certainly behind the controversial Hiroshima witness poetry submitted to literary journals under the name Yasusada.

‘Mock hoaxes’ are often highly literary because they are executed by experienced writers with a genuine artistic end in mind. James Norman Hall, the creator of Fern Gravel, for example, was intent on finding a new, softer outlet for a narrative voice honed on adventure stories and wartime memoir. He believed passionately in the value of the work that his alter-ego was producing and, although it was childish and unsophisticated, critics agree that there is something more substantial than mere charm to Fern’s melancholic coming-of-age poems. Of course, not every hoax fits neatly into only one of McHale’s three categories, but his groupings do help to identify the main reasons why the peculiar and often underrated writers whose stories are told in these pages did what they did.

From the aristocratic sex addict who wrote outrageous things about the empress Cixi in fin de siècle Shanghai to the lonely middle-aged lady who invented for herself a dying, memoir-writing son, all human life is here, and the one thing they nearly all have in common is that they are writing from the margins. Even if they have had a materially privileged start in life or are possessed of a sharp intelligence, at some point each hoaxer has been made to feel excluded from the world they would be part of. An astonishing number of them were missing a parent. Most had once been praised for their literary abilities, but had failed to find success by conventional means. And almost all have a community – real or imagined – whose ways and boundaries they are seeking to protect in their writings. The ‘entrapment hoaxers’ try to safeguard what they see as the authentic values of their social or academic kin against attacks from new-fangled trends. The ‘genuine hoaxers’ seek a way to make an imagined world seem real enough for the reading public to buy into. And for those post-modern experimentalists who produce ‘mock hoaxes’, even their hyper-identity as a writer is meant to be included in the ‘reality’ of their text.

Reality itself becomes a problem, however, the further one looks into these texts and the more one asks of literature as a gate-keeper of truth. The assumption that some kinds of writing are truer than others is not as straightforward as it might sound. Can it categorically be said that novels are untrue and memoirs are true? Surely not, as anyone who has basked in the wisdom of a great work of art (written, painted or played) will know that the only way to convey what it is like to be alive is to conjure something aesthetically complex enough to approximate to our experience of reality. Because reality, after all, is nothing if not a mystery. Writers of memoir, biography and straight non-fiction have a more tenuous claim on the faithful transmission of truth than might at first be supposed because stories about people, places and events can only ever be passed down through the imperfect, partial minds of others.

A recent example of the memoirist’s art coming under theoretical and popular scrutiny is the infamous American author James Frey, whose bestselling book A Million Little Pieces claimed to tell the true, harrowing tale of his descent into drug and alcohol abuse and his remarkable self-guided recovery. The book was a huge success on publication in the US in 2003, and the author was held up by Oprah Winfrey as a beacon for others on the road to recovery. Frey’s writing style was spare, seemingly immensely candid and instantly readable, and he told stories of extreme physical and mental hardship. Much of what he wrote seemed almost too intense to be true, and indeed it was. But when he was had up for fabricating portions of the book, he argued that the essence of the thing was absolutely real and he had merely changed certain details to better convey the truth of what happened, and to protect the other people involved. There were also rumou

rs of Frey first submitting his manuscript as fiction but being advised that a ‘misery memoir’ would sell better . . .

The rise and rise of the late-twentieth-century genre known as ‘misery memoir’ is a peculiarity of contemporary publishing which deserves a closer look, not least because the popularity of books with titles like Please, Daddy, No! say a great deal about who we are as readers and what makes us so susceptible to hoaxing. Uplifting stories of personal hardship are clearly very appealing to us and always have been. The defining story of the Christian age gives a clue as to how much we need to witness the pain of others, and as well as the Bible’s cast of auxiliary sufferers (Job, Noah et al) most other religions have their own fables about people or gods enduring trials and difficult journeys. Classical tragedians responded to this, understanding the value of catharsis in such tales, and in English literature from Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton to Bunyan, Defoe and Dickens, there has been a steady stream of popular fiction about men whose physical and mental realities are defined by punishment or abuse. It was not until the twentieth century and the emergence of modern publishing, however, that the idea of actually faking ‘real’ bad experiences took hold.

The now-forgotten hoaxer Joan Lowell in 1920s New York fooled the publishers Simon & Schuster into believing she had been the sole female on a years-long merchant seamen’s voyage and as a result engaged in all manner of unladylike acts. Other phoney memoirists, like the pseudonymous Cleone Knox with her faux-eighteenth century Diary of a Young Lady of Fashion or the ‘Anonymous’ author of the cult drug-diary Go Ask Alice who turned out to be a middle-aged Mormon with an axe to grind, hid behind their lurid creations until they could no longer sustain the deceit.

Pretending to have been involved in illicit escapades as a teenage girl hardly compares to the most shocking subsection of fake memoirists, the Holocaust pretenders: Binjamin Wilkomirski, Misha Defonseca, Herman Rosenblat and Helen Demidenko each had different reason for pretending to have been a victim – or in Demidenko’s case, supporter – of Hitler’s regime. Surprisingly, what can be pieced together of their ‘real’ true stories often reveals biographies which were every bit as full of adventure, sacrifice and passion as their assumed selves, only without the massively emotive signifier of Nazism.

Telling Tales

Telling Tales